The Evolution of Understanding Moral Injury

Five years ago, as the COVID-19 pandemic began overwhelming healthcare systems worldwide, a term once confined to military psychology began appearing in mainstream medical discussions: moral injury. Today, in late 2025, we stand at a transformative moment. The inclusion of moral problems in the DSM-5-TR represents not just diagnostic evolution, but validation of experiences that healthcare workers, veterans, and first responders have long struggled to name.

As we’ve explored in our previous examination of moral injury during the pandemic, what began as crisis recognition has evolved into systematic clinical understanding. This comprehensive guide synthesises the latest research, assessment tools, and treatment approaches, offering both professionals and those experiencing moral injury a complete resource for understanding and addressing this complex condition.

Understanding Moral Injury: Core Definitions and Concepts

What Is Moral Injury?

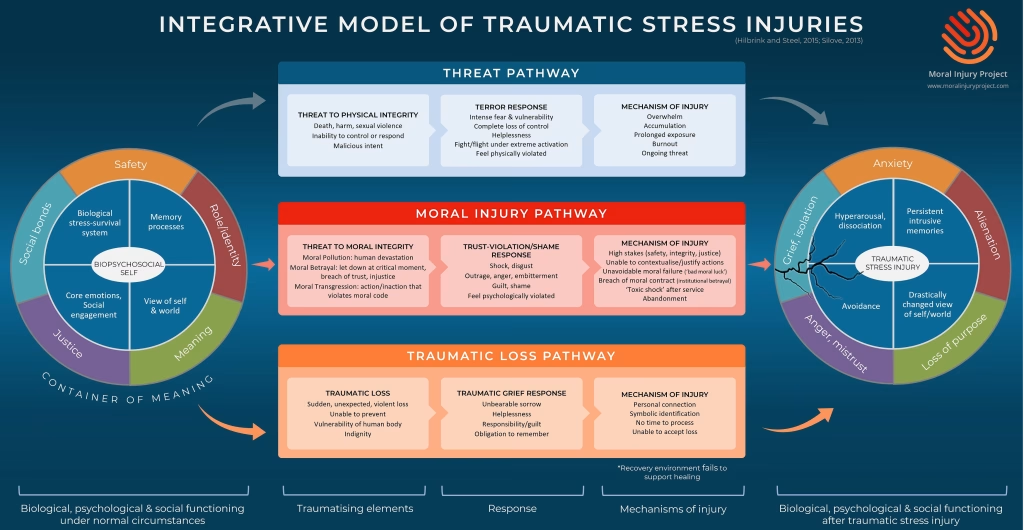

According to the Moral Injury Project at Syracuse University, moral injury is damage done to the soul of the individual. It occurs when someone perpetrates, witnesses, or fails to prevent acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations. Unlike physical wounds or even psychological trauma rooted in fear, moral injury strikes at the core of one’s identity as a moral being.

The Ethics Centre of Australia emphasises that moral injury involves a betrayal of what is right, either by oneself or by someone in a position of legitimate authority, in a high-stakes situation. This betrayal leads to profound psychological, social, and spiritual suffering that extends beyond traditional mental health categories.

The DSM-5-TR Recognition: A Historic Milestone

In September 2025, the American Psychiatric Association published a groundbreaking update to the DSM-5-TR, formally recognising moral problems under code Z65.8: “Moral, Religious, or Spiritual Problem.”¹ This classification acknowledges that moral problems “include experiences that disrupt one’s understanding of right and wrong, or sense of goodness of oneself, others or institutions.”

This recognition matters because it:

- Legitimises the distinct nature of moral suffering

- Enables specific clinical documentation and treatment planning

- Facilitates insurance coverage for specialised interventions

- Promotes research through standardised classification

Distinguishing Moral Injury from Related Conditions

As detailed in The Lancet Psychiatry, moral injury differs fundamentally from other psychological conditions:²

Moral Injury vs PTSD:

- PTSD stems from life-threat and fear

- Moral injury arises from moral violations

- PTSD involves hypervigilance and avoidance of triggers

- Moral injury involves shame, guilt, and spiritual crisis

Moral Injury vs Burnout:

- Burnout results from chronic workplace stress

- Moral injury stems from specific moral violations

- Burnout causes exhaustion and cynicism

- Moral injury causes deep shame and loss of meaning

Moral Injury vs Depression:

- Depression involves persistent low mood and anhedonia

- Moral injury specifically relates to moral transgressions

- Depression may occur without precipitating events

- Moral injury always links to identifiable moral conflicts

The Australian Landscape: Current State of Moral Injury

Healthcare Worker Moral Injury Post-Pandemic

According to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs comprehensive assessment, Australian healthcare workers continue experiencing significant moral injury from pandemic-related decisions and ongoing system pressures.³

Key findings include:

- 60% of healthcare workers report ongoing moral distress

- 45% of nurses experience higher rates than other professionals

- 1 in 9 nurses leaving the profession cite moral injury factors

- Systemic issues persist beyond pandemic acute phase

Research published in BMC Psychiatry identifies specific ongoing triggers:⁴

- Chronic understaffing forcing compromised care

- Resource allocation decisions

- Institutional policies conflicting with patient needs

- Inability to provide culturally appropriate care

Veterans and Military Personnel

Open Arms reports that Australian veterans experience moral injury from:⁵

- Witnessing civilian casualties

- Following orders conflicting with personal values

- Inability to help local populations

- Perceived betrayal by leadership or government

- Transition challenges to civilian life

The DVA’s rapid evidence assessment highlights that military moral injury often co-occurs with PTSD but requires distinct treatment approaches focusing on:

- Values reconciliation

- Meaning-making

- Spiritual repair

- Community reintegration

First Responders: The Overlooked Population

Recent Australian research reveals first responders face unique moral injury risks:

- Police: Use of force decisions, witnessing preventable tragedies

- Paramedics: Triage decisions, resource limitations

- Firefighters: Inability to save lives despite best efforts

For more on supporting these populations, see our guide on First Responder Mental Health.

Recognising Moral Injury: Presentation, Symptoms, and Assessment

Moral Injury Presentation

Moral injury does not usually look like a single symptom; it appears as a pattern across emotions, relationships, and the body.

At its core is a rupture between what a person believes is right and what they were compelled to do, witness, or endure. This “fractured inner compass” can leave people feeling internally divided — torn between their values and their lived reality — which then ripples outward into how they feel, connect with others, and function day to day.

Emotionally, moral injury often presents as anger, shame, grief, or anxiety — sometimes shifting rapidly between them. Relationally, people may withdraw or feel alienated from others, as trust in themselves or institutions has been damaged. Physically and psychologically, disrupted sleep, nightmares, and a self-reinforcing cycle of low mood, guilt, and withdrawal can emerge.

Importantly, these responses are not signs of weakness or personal failing; they are understandable reactions to experiences that have violated deeply held moral beliefs.

Core Symptoms and Experiences

The Moral Injury Project identifies key symptom clusters:⁶

Emotional Symptoms:

- Intense guilt and shame

- Anger at self, others, or institutions

- Profound sadness and grief

- Emotional numbing or disconnection

Cognitive Symptoms:

- Persistent negative self-judgments (“I’m unforgivable”)

- Loss of trust in authority and institutions

- Questioning previously held beliefs

- Intrusive thoughts about the morally injurious event

Behavioural Symptoms:

- Social isolation and withdrawal

- Self-punishing behaviours

- Substance use as coping

- Difficulty in relationships

Spiritual/Existential Symptoms:

- Loss of meaning and purpose

- Questioning faith or spiritual beliefs

- Feeling condemned or unworthy of forgiveness

- Existential despair

Social Symptoms:

- Difficulty trusting others

- Alienation from previously important communities

- Inability to share experiences

- Feeling fundamentally different from others

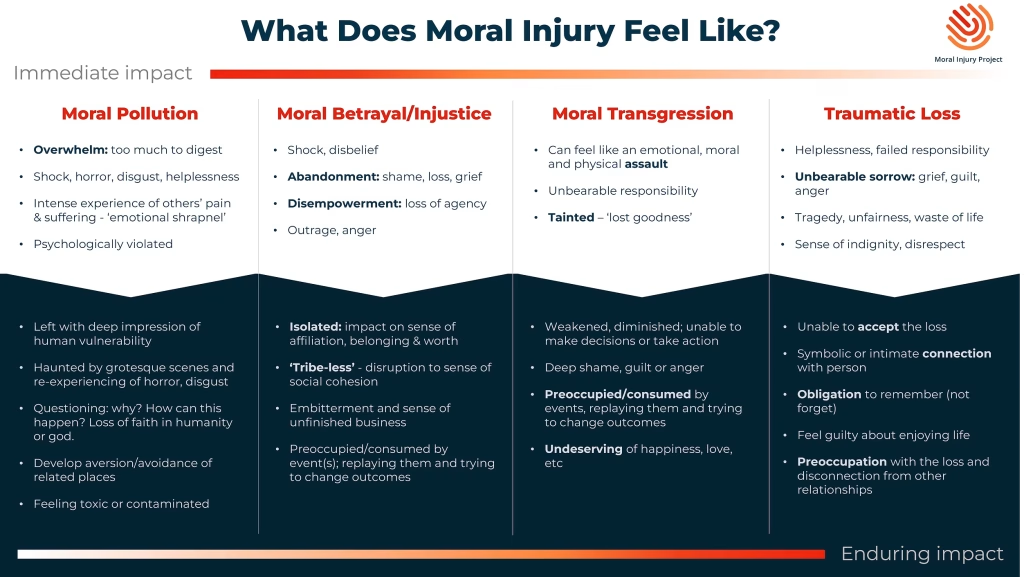

The Phenomenology: What Moral Injury Feels Like

Drawing from lived experience research, moral injury manifests as:

Immediate Impact:

- Moral Pollution: Feeling contaminated or dirty

- Moral Betrayal: Shock at violations of trust

- Moral Transgression: Horror at one’s actions

- Traumatic Loss: Grief over lost innocence

Enduring Impact:

- Isolation: “No one could understand”

- Preoccupation: Constant rumination

- Obligation: Compulsive need to atone

- Incompleteness: Sense of unfinished business

Assessment Tools and Measures

The Moral Injury and Distress Scale (MIDS)

The MIDS, released in 2023, provides:⁷

- Event-specific assessment

- Validated cut-points for clinical significance

- Cross-population validity

- Free availability for clinicians

The Moral Injury Outcome Scale (MIOS)

Developed through international collaboration, the MIOS offers:⁸

- 14-item assessment

- Two factors: Shame-Related and Trust-Violation-Related outcomes

- Cross-cultural validity

- Integration with treatment planning

Clinical Interview Considerations

When assessing moral injury, clinicians should:

- Create a non-judgmental space

- Ask about specific events violating values

- Explore role (perpetrator, witness, betrayed)

- Assess spiritual/existential impact

- Document using DSM-5-TR Z65.8 code

- Screen for co-occurring conditions

Evidence-Based Treatment Approaches

Established Adaptations of Trauma Therapies

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) for Moral Injury

Recent trials demonstrate CPT effectiveness when adapted for moral injury:⁹

- Focus on moral assumptions rather than just danger assumptions

- Extended work on contextual factors

- Integration of self-forgiveness modules

- Attention to values clarification

Key Modifications:

- Challenging moral absolutism

- Exploring contextual constraints

- Addressing hindsight bias

- Reconstructing moral identity

Prolonged Exposure (PE) with Values Integration

PE adaptations for moral injury include:¹⁰

- Imaginal exposure to morally injurious events

- In-vivo exercises reconnecting with values

- Behavioural activation targeting moral repair

- Community reengagement activities

Specialised Moral Injury Interventions

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury (ACT-MI)

ACT-MI represents a paradigm shift in moral injury treatment:¹¹

- Duration: 15 sessions (individual and group hybrid)

- Focus: Living according to values despite moral pain

- Core Processes:

- Acceptance of moral emotions without avoidance

- Cognitive defusion from self-condemning thoughts

- Values clarification and commitment

- Mindful awareness of present-moment experience

- Self-as-context work for identity flexibility

Adaptive Disclosure

Originally developed for military populations, now expanded:¹²

- 12-session protocol

- Imaginal conversations with compassionate moral authority

- Empty chair techniques for forgiveness

- Letters to self, others, or deceased

- Integration of meaning-making

Impact of Killing (IOK)

Specifically for killing-related moral injury:¹³

- 10 sessions post-PTSD treatment

- Focus on forgiveness planning

- Letter writing exercises

- Values honour ceremonies

Building Spiritual Strength

Addressing spiritual dimensions:¹⁴

- 8-session group format

- Chaplain involvement

- Exploration of forgiveness

- Restoration of spiritual connections

Emerging and Innovative Approaches

Trauma-Informed Guilt Reduction (TrIGR)

Brief intervention showing promise:¹⁵

- 6 sessions focusing on guilt and shame

- Cognitive reappraisal of responsibility

- Values identification and action planning

- Behavioural experiments testing beliefs

Community-Based Interventions

The Moral Engagement Group (MEG) model emphasises:¹⁶

- Collective healing approaches

- Public testimony and witness

- Community service as moral repair

- Peer support networks

Integrative Approaches

Combining modalities for comprehensive care:

- Individual therapy for symptom management

- Group therapy for connection and normalisation

- Spiritual care for existential concerns

- Peer support for shared understanding

- Family therapy for relational healing

→ For more on trauma treatments, see our guide to Evidence-Based Trauma Treatments.

Systemic and Organisational Interventions

Healthcare System Reforms

Addressing root causes requires systemic change:¹⁷

Immediate Interventions:

- Ethics consultation services

- Moral distress rounds

- Peer support programmes

- Leadership communication protocols

Long-term Reforms:

- Adequate staffing ratios

- Resource allocation transparency

- Values-based decision frameworks

- Culture change initiatives

Professional Development:

- Moral injury education in training

- Continuing education requirements

- Supervision models addressing moral dimensions

- Self-care as professional responsibility

Military and Veteran Support Systems

The DVA recommends:¹⁸

- Pre-deployment moral injury education

- In-theatre support systems

- Transition programmes addressing moral injuries

- Long-term follow-up protocols

First Responder Initiatives

Emerging best practices include:

- Critical incident debriefing with moral focus

- Peer support trained in moral injury

- Chaplaincy and spiritual care access

- Organisational culture addressing moral stress

Special Considerations and Populations

Cultural and Spiritual Dimensions

Moral injury intersects with cultural values:¹⁹

- Indigenous concepts of spiritual wounds

- Cultural variations in guilt and shame

- Religious frameworks for forgiveness

- Community-based healing traditions

Gender Considerations

Research reveals gender differences:

- Women report higher guilt, men higher anger

- Different coping strategies

- Varying help-seeking behaviours

- Distinct treatment preferences

Developmental Perspectives

Age and development influence moral injury:

- Young adults: Identity formation disruption

- Mid-life: Values reassessment

- Older adults: Life review complications

Recovery and Post-Traumatic Growth

The Recovery Journey

Recovery from moral injury is non-linear:²⁰

- Acknowledgment: Recognising moral injury

- Expression: Sharing the experience

- Processing: Working through emotions

- Integration: Incorporating into life narrative

- Transformation: Finding new meaning

- Service: Using experience to help others

Facilitating Post-Traumatic Growth

Some individuals experience growth through:

- Clarified values and priorities

- Deepened compassion and empathy

- Renewed sense of purpose

- Spiritual development

- Commitment to preventing others’ moral injuries

Peer Support and Lived Experience

The power of shared experience:²¹

- Reduces isolation and shame

- Provides hope through modelling

- Offers practical coping strategies

- Creates meaning through service

Future Directions and Research

Priority Research Areas

The field requires investigation into:²²

- Biomarkers distinguishing moral injury from PTSD

- Cultural adaptations of interventions

- Prevention strategies for high-risk professions

- Long-term outcomes and trajectories

- Intergenerational transmission

Innovation in Treatment

Emerging approaches under development:

- Virtual reality for perspective-taking

- AI-assisted values clarification

- Psychedelic-assisted therapy protocols

- Community healing circles

- Art and narrative therapies

Policy and Advocacy

Critical policy priorities:

- Insurance coverage for moral injury treatment

- Workplace mental health standards

- Professional education requirements

- Research funding allocation

- Public awareness campaigns

Practical Resources and Support

For Individuals Experiencing Moral Injury

Immediate Steps:

- Recognise you’re not alone

- Name the experience as moral injury

- Seek professional support

- Connect with peers who understand

- Be patient with the healing process

Self-Care Strategies:

- Journaling about values and experiences

- Mindfulness and meditation practices

- Creative expression through art or writing

- Physical activity and nature connection

- Spiritual or philosophical exploration

For Healthcare Professionals

Assessment Resources:

- Download MIDS assessment tool

- Access MIOS through Phoenix Australia

- Use DSM-5-TR Z65.8 coding

- Screen for co-occurring conditions

- Document thoroughly for treatment planning

Treatment Planning:

- Match intervention to individual needs

- Consider group and individual modalities

- Integrate spiritual care when appropriate

- Address systemic factors

- Monitor for risk factors

Professional Development:

- Attend moral injury training workshops

- Join professional interest groups

- Access supervision for complex cases

- Engage in self-care to prevent vicarious moral injury

For Organisations

Implementation Strategies:

- Conduct organisational assessment

- Develop moral injury policies

- Train leadership and staff

- Establish support systems

- Monitor and evaluate outcomes

Creating Psychologically Safe Workplaces:

- Open communication channels

- Transparent decision-making

- Values-aligned policies

- Adequate resources

- Support for staff wellbeing

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The journey from hidden wound to clinical recognition represents tremendous progress, yet much work remains. The DSM-5-TR inclusion of moral problems validates experiences long dismissed or misunderstood. For the healthcare workers who made impossible decisions during the pandemic, veterans carrying the weight of war, and first responders witnessing daily tragedies, this recognition offers hope for understanding and healing.

As we move forward, addressing moral injury requires more than individual treatment—it demands systemic change, organisational accountability, and cultural transformation. The path from moral injury to moral repair is challenging but possible. Through continued research, clinical innovation, and commitment to addressing root causes, we can support those whose service to others has come at profound personal cost.

Recovery involves not forgetting or minimising moral injuries, but integrating them into a life narrative that includes growth, meaning, and renewed purpose. As the Moral Injury Project reminds us, moral injury reflects the depth of human conscience—our capacity to care deeply about right and wrong. In acknowledging and treating moral injury, we honour both the suffering and the humanity of those affected.

The inclusion of moral injury in our clinical frameworks represents not an end but a beginning—an opportunity to transform how we understand and respond to the moral dimensions of human suffering. For all those carrying moral wounds, know that recognition, understanding, and healing are possible. The journey may be long, but you need not walk it alone.

Australian Resources and Support

Crisis Support:

- Lifeline Australia: 13 11 14 (24/7)

- Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636

- Suicide Call Back Service: 1300 659 467

- MensLine Australia: 1300 78 99 78

Specialised Support:

- Open Arms (Veterans & Families): 1800 011 046

- Phoenix Australia: www.phoenixaustralia.org

- Black Dog Institute: www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

- Centre for Moral Injury (when established): Check Phoenix Australia for updates

Professional Resources:

- Phoenix Australia Moral Injury Resources: phoenixaustralia.org/resources/moral-injury/

- DVA Moral Injury Information: dva.gov.au

- Australian Psychological Society: psychology.org.au

- RANZCP Resources: ranzcp.org

Assessment Tools:

- MIDS Download: Available through NCPTSD

- MIOS Access: ISTSS

- Moral Stress Amongst Healthcare Workers During COVID-19: A Guide to Moral Injury (Phoenix Australia)

Education and Training:

- Phoenix Australia Training: Professional development courses

- University Programs: Check major universities for specialised courses

- Online Learning: Coursera and FutureLearn trauma courses

- Professional Workshops: Check professional associations

Related Articles:

- Understanding Moral Injury During COVID-19

- Beyond PTSD: Towards a Trauma-Informed Workplace

- The Silent Epidemic: Confronting the Realities of Occupational Burnout

- Evidence-Based Trauma Treatments in 2025

- What Is Digital Burnout? 7 Evidence-Based Strategies

- Echoes of Trauma: Recognising and Addressing Signs of PTSD

- Nervous System Regulation: Guide to Emotional Balance & Anxiety Relief

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5-TR Update: Supplement to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; September 2025.

2. Williamson V, Stevelink SAM, Greenberg N. Moral injury: the effect on mental health and implications for treatment. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(6):453-455.

3. Metcalf O, Phelps A, Watson L, Varker T. The current status of moral injury: A narrative review and Rapid Evidence Assessment. Phoenix Australia – Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health; 2022.

4. Čartolovni A, Stolt M, Scott PA, Suhonen R. Moral injury in healthcare professionals: A scoping review and discussion. Nurs Ethics. 2021;28(5):590-602.

5. Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling. Moral Injury. Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs; 2025.

6. The Moral Injury Project. What is Moral Injury. Syracuse University; 2025.

7. Norman SB, Griffin BJ, Pietrzak RH, et al. The Moral Injury and Distress Scale: psychometric evaluation and initial validation in three high-risk populations. Psychol Trauma. 2024;16(3):280-291.

8. Litz BT, Plouffe RA, Nazarov A, et al. Defining and Assessing the Syndrome of Moral Injury: Initial Findings of the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:923928.

9. Held P, Klassen BJ, Brennan MB, Zalta AK. Using prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy to treat veterans with moral injury-based PTSD. Behav Ther. 2018;49(4):607-616.

10. Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, Marmar CR. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: a review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2015;314(5):489-500.

11. Farnsworth JK, Borges LM, Walser RD, et al. Case Conceptualizing in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:910414.

12. Gray MJ, Schorr Y, Nash W, et al. Adaptive disclosure: an open trial of a novel exposure-based intervention for service members with combat-related psychological stress injuries. Behav Ther. 2012;43(2):407-415.

13. Maguen S, Burkman K, Madden E, et al. Impact of killing in war: a randomized, controlled pilot trial. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(9):997-1012.

14. Harris JI, Usset T, Voecks C, et al. Spiritually integrated care for PTSD: a randomized controlled trial of “Building Spiritual Strength.” Psychiatry Res. 2018;267:420-428.

15. Norman SB. Trauma informed guilt reduction therapy: treating guilt and shame resulting from trauma and moral injury. London: Academic Press; 2019.

16. Starnino VR, Sullivan JE, Angel CT, et al. Moral Engagement Group: A trauma-informed intervention for moral injury. Soc Work Groups. 2023;46(2):145-160.

17. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

18. Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Framework for Moral Injury Support. Australian Government; 2023.

19. Gone JP, Hartmann WE, Pomerville A, et al. The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):20-35.

20. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inquiry. 2004;15(1):1-18.

21. Hundt NE, Robinson A, Arney J, et al. Veterans’ perspectives on benefits and drawbacks of peer support for posttraumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 2015;180(8):851-856.

22. Frankfurt S, Frazier P. A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Mil Psychol. 2016;28(5):318-330.

Expert Review: This article has been reviewed by clinical psychologists specialising in trauma and moral injury treatment.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. If you are experiencing symptoms of moral injury or other mental health concerns, please consult with a qualified mental health professional.

Copyright Notice: © 2025 Mind Health Australia. This article may be shared with attribution to mindhealth.com.au